Can Fungi Solve Our Buckthorn Problem?

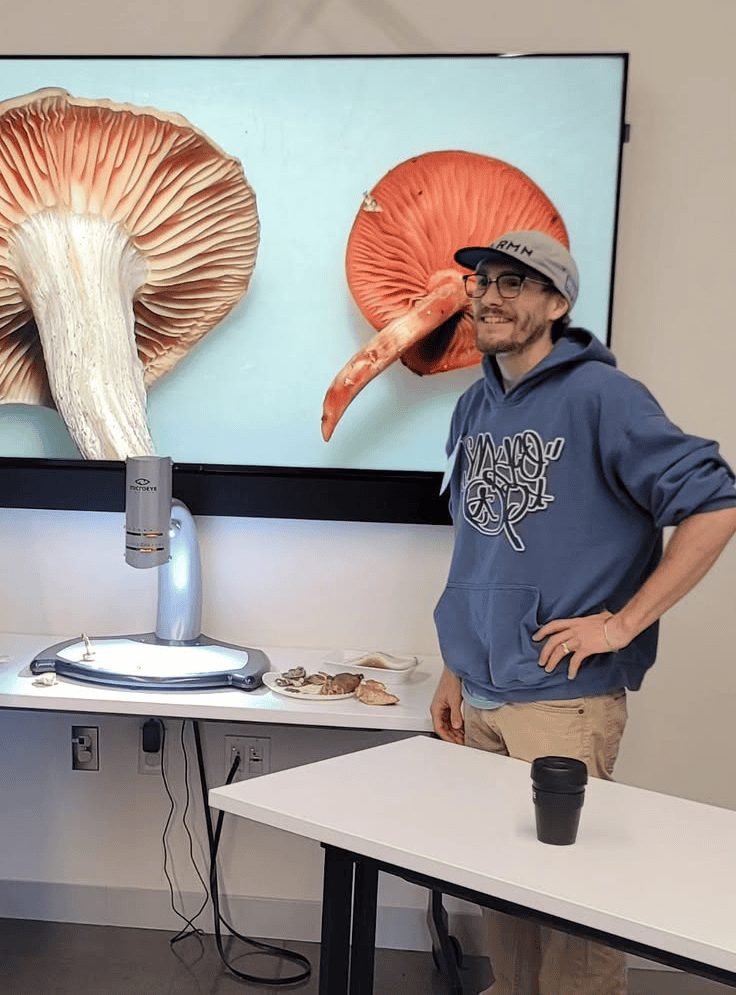

By Ryan Franke, 2024 MMS Graduate Scholarship Winner

From brewing beer to producing antibiotics, modern society relies on fungal life processes to fulfill our desires and overcome our obstacles. How about the buckthorn problem? Can fungi help us get rid of invasive buckthorn? This is the central question of my research in the UMN Forest Pathology lab under the direction of Professor Robert (Bob) Blanchette.

Developing a Mycoherbacide

Our approach to developing a mycoherbicide for buckthorn can be summarized in three steps:

- Collect fungi from dead and dying buckthorn and other diseased hardwoods.

- Test this collection of fungi for their ability to cause disease in healthy buckthorn.

- Develop a methodology for application of the fungi to buckthorn in the field that can be used by land managers.

Last summer, fellow researchers in the Blanchette lab and I answered the call to visit fifteen sites across Minnesota and Wisconsin with dead and dying buckthorn. We were tipped off to a handful of these locations by citizen scientists, and many more were brought to our attention by Minnesota and Wisconsin state personnel. Dieback from the top of the stem toward the base of the trunk to varying degrees was the most frequently observed symptom across all sites.

We also found localized cankers originating at branch stubs at some of the sites. A canker is an area of dead inner bark that has been walled off from healthy tissue by thick, reactionary callus tissue. Back in the lab, we excised small pieces of diseased tissue, placed them onto agar media and waited for the resident fungi to emerge and spread across the petri dish. We extracted the DNA of each fungal isolate and sequenced the ITS “barcode” region of DNA, which can be used to identify most fungi to a particular species.

Sidenote: Biological Nomenclature

If you’re a little fuzzy on biological nomenclature, here’s a familiar example to help you gain some traction for the next piece of information: Morchella esculenta, the prized edible delicacy (unfortunately, not collected from buckthorn) belongs to the genus, Morchella and is more narrowly defined by its species name, esculenta. Presently, we have identified 294 isolates (individual fungi) as 89 unique species belonging to 64 genera (plural of genus). It’s fascinating to know that so many different fungi are associated with dead and dying buckthorn.

Now, the task at hand is to separate the chaff (decomposers, weak pathogens, endophytes) from the wheat (fungi capable of bringing ruin to vigorously growing buckthorn). The first step to determine whether a species in our collection may be pathogenic to buckthorn was to look for evidence in the scientific literature of serious pathogenicity on woody plants. This review helped us narrow down the list of potential candidates for biocontrol from 89 to 29 species.

Transplanting Buckthorn for Research

During an unseasonably warm day last October, I uprooted 300 buckthorn saplings from their cozy residence on the UMN campus and transplanted them into our greenhouse. Despite being leafed out, every single tree survived transplanting. What a tenacious plant!

Since then, I’ve been using the saplings to screen our likely candidate fungi from dead and dying buckthorn for their ability to cause disease in healthy buckthorn. To do this, I grow the fungi on birch wood chips. Once the wood chips are myceliated, I make a wound in the sapling and insert the myceliated wood chip into the wound. After introducing the inoculum, I wrap the wound site with parafilm wax paper to prevent the fungus from drying out, and secondly wrap with duct tape to eliminate potential harm to the fungus by UV radiation. After 3 months, I will harvest the saplings and measure the size of the canker surrounding the wound, which will serve as my metric for pathogenicity.

A Track Record of Success with Mycoherbicides

In addition to fungi isolated from dead and dying buckthorn, I’ve included several generalist fungal pathogens isolated from non-buckthorn hosts in the greenhouse inoculation study. One of these pathogens, Chondrostereum purpureum has been licensed as the active ingredient in a few different commercial mycoherbicide products in Canada over the past 20 years. These products have been used to prevent the resprouting of hardwood stumps, including invasive buckthorn. In fact, this fungus has been particularly well studied as a mycoherbicide, with research showing no significant effects on the environment beyond its targets.

Although we are pleased to be testing multiple Chondrostereum purpureum isolates that we have collected locally, this fungus is just one of 50 species that we are in the process of testing. This summer, we will begin experimenting with various inoculum formulations as applied to cut buckthorn stumps. So, can fungi help us get rid of buckthorn? I’d say the odds are pretty good.

About Ryan Franke